On March the 3rd of this year the Fed had to step in and bail out the repo market again. Yet, this time wasn't enough, even though their repo operations were supposedly temporary.

There was a huge uptick in demand and in the level of repo operations the Fed was committing to.

However, my main point here is we often forget the repo market shouldn't require the Fed's permanent involvement. The repo market needing this help only shows our system is broken.

In this article, I explain March's repo market number, how the repo market actually works, and its potential problems.

Overview Of The Numbers

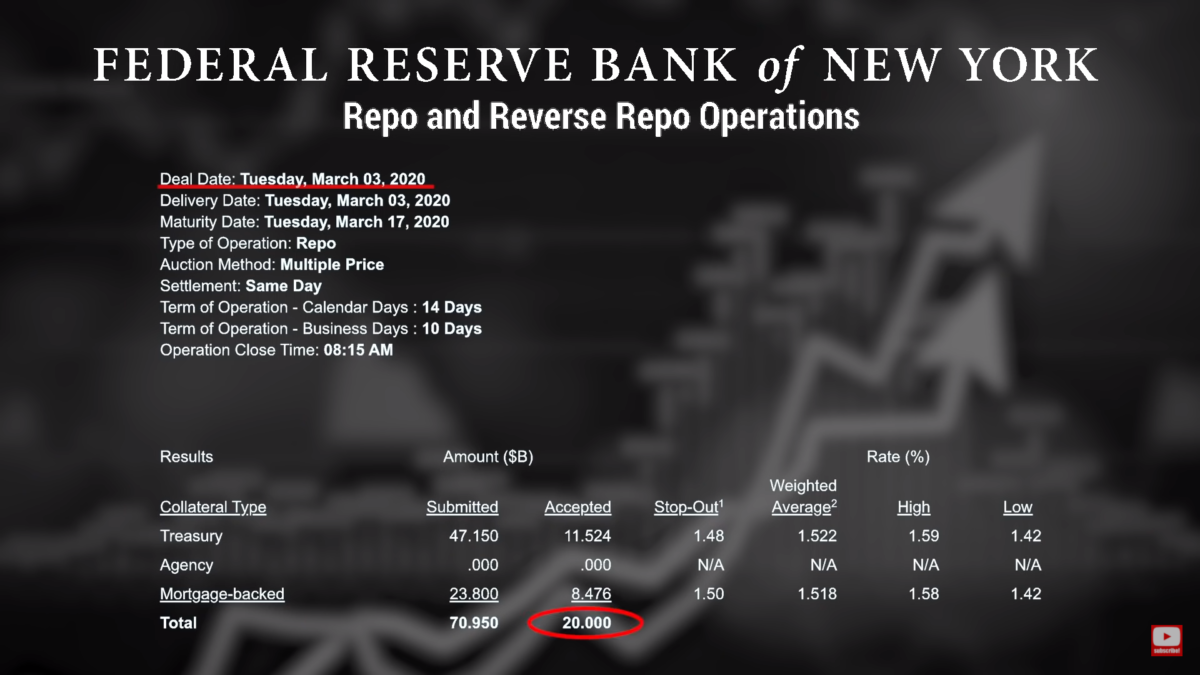

On March 3rd of this year, the Fed was offering up $20 billion in term repos, and there were $70 billion in demand, meaning $50 billion oversubscribed on the term repos.

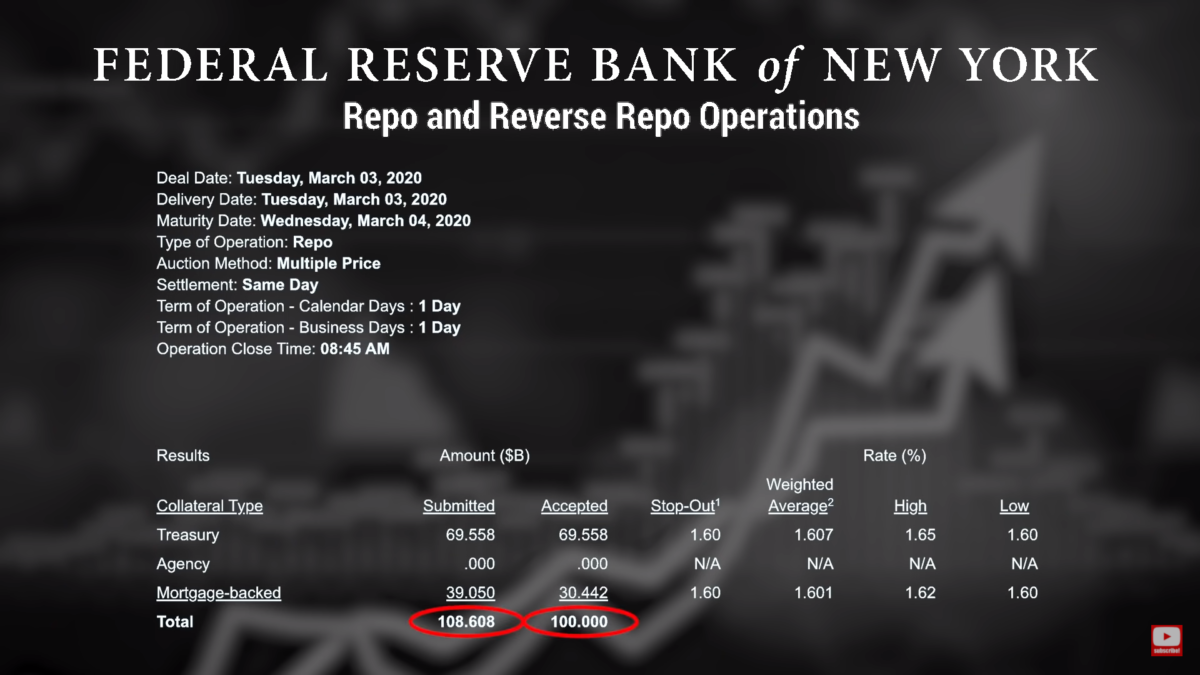

The accepted overnight repos were $100 billion, but there were $108 billion of demand.

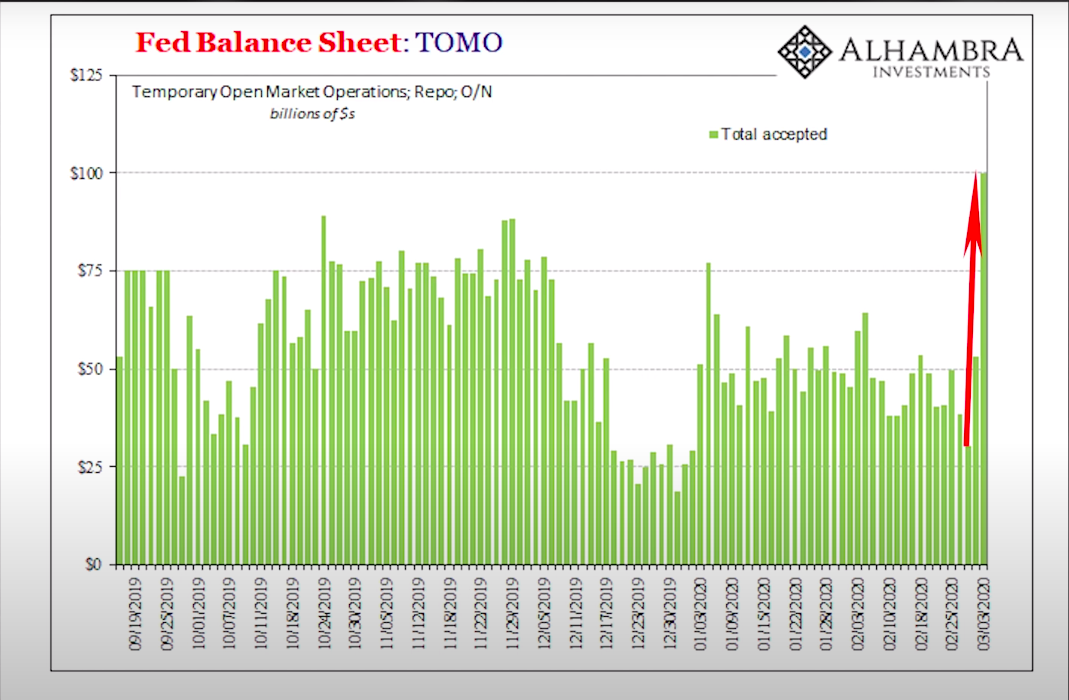

So, not as oversubscribed, but here is an image where you can see how the amount of overnight repos is going up dramatically. Because of that excess demand, the repo rates spiked up to 1.8%.

So, not as oversubscribed, but here is an image where you can see how the amount of overnight repos is going up dramatically. Because of that excess demand, the repo rates spiked up to 1.8%.

I saw on Twitter on March 3rd of this year that a lot of the CNBC “analysts” were saying the reason the Fed might have cut rates down by 50 basis points was because of the repo market pressures, and that the 50 basis point cut would relieve some of those pressures.

Also on Twitter, during the month of March, a couple of people asked me this directly, and I responded by saying that I didn't think the interest rate drop would relieve any of the pressures on the repo market.

That's due to my conversation with Jeff Snyder.

So, what really happened that morning in the repo market?

It is officially stiff drink time. Because even though the Fed dropped interest rates by 50 basis points, again, that morning, it was oversubscribed.

The Fed was offering a hundred billion for the overnight repos, but there was $111 billion in demand.

Even though they dropped 50 basis points, that still didn't fix or even help the repo market at all, just like I predicted that night on Twitter.

The Fed Injecting Money Into The Repo Market: How Does That Actually Work?

There's a lot of confusion on Twitter about The Fed injecting money into the system. That's what you always hear but it's not exactly true.

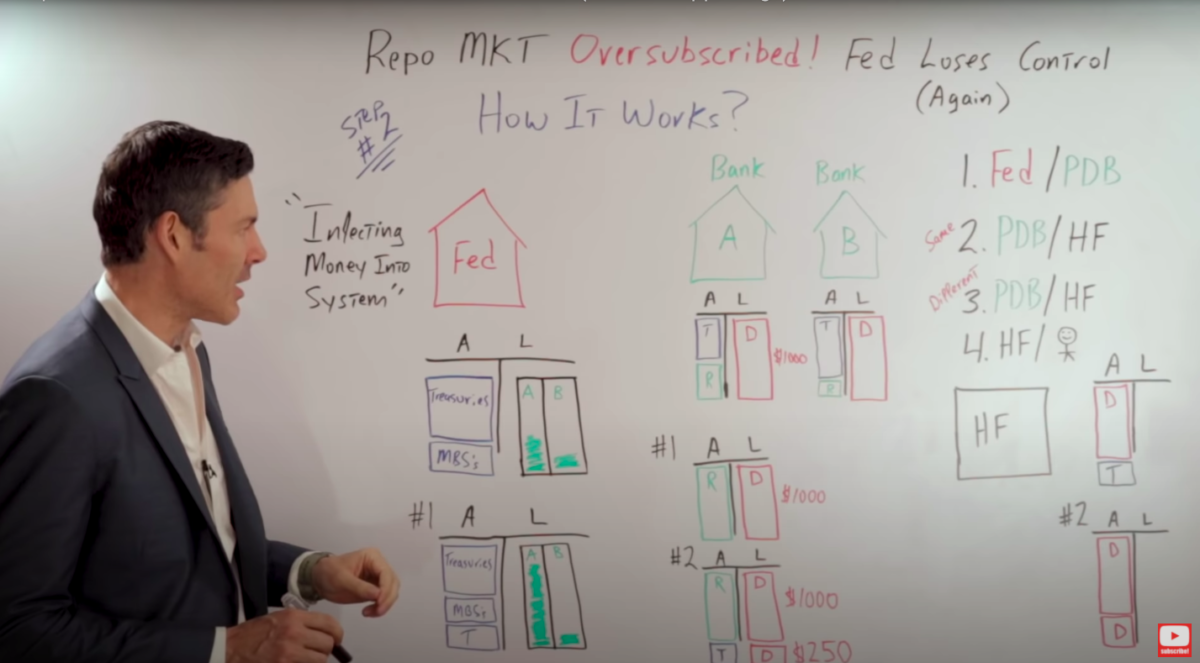

There's a lot of nuance to this that people just don't understand. So to get you up to speed, I'll explain to you the three types of transactions there are with this chart I drew.

The red house represents the Federal Reserve's balance sheet with its assets and liabilities. On the asset side(A), they usually have treasuries and mortgage-backed securities.

On the liabilities side (L), there are the deposits from the banks under the feds umbrella, typically the primary dealer banks. That's where they keep their reserves.

Those cash reserves are a liability on the fed's balance sheet, just like customer deposits are a liability on a normal bank's balance sheet.

Now, the two green houses are the primary dealer banks. The asset side of their balance sheet has treasuries and the reserves, and on the liabilities, they have customer deposits.

I know this is a very simple balance sheet. In one video I did, there was a comment where someone said, “Oh, that's not what a bank's balance sheet looks like. It's far more complex.”

And yes, I get it. But right now, I'm just trying to explain the basics. So this is applicable for what we're trying to achieve today.

So, on the balance sheet drawn you can see treasuries, reserves, and deposits. Same thing for bank B.

In the same drawing, take a look over to the hedge funds (HF), for this case, I'm just going to focus on the asset side of their balance sheet. This would be, the deposits that are liabilities of the banks, and some treasuries.

Some this works like this…

-

Transaction #1: FED/Primary Dealer Bank ‘A'

In our first example transaction, The Fed does a repo with primary dealer bank A.

That bank gives the Fed those treasuries as collateral, and they go onto the fed's balance sheet. Then, the Fed puts more reserves into the account of that primary dealer bank.

The way the balance sheet changes. On the asset side, the Fed has more treasuries, and then, on the liabilities side, the primary dealer banks have more reserves than they had before.

What does that do to the primary dealer bank A's balance sheet?

Well, instead of having treasuries on the asset side, now they have all reserves, and the deposits or the liabilities don't change at all.

If we had a thousand dollars of deposits to start, we still have the same amount of deposits. It is crucial that you understand that.

When we talk about money getting into the system, if the money is on The Fed's balance sheet in the form of reserves, it is not in the system. The only way there can be additional funds in the system is if the actual deposits increase.

If the transaction is exclusively between The Fed and the primary dealer bank, it doesn't increase the amount of liquidity that we have in the actual system itself.

-

Transaction #2: Primary Dealer Bank A/Hedge Fund

The second example of transactions is between primary dealer bank A and a hedge fund.

The hedge fund, we'll assume, has an account with the primary dealer bank, that's very important. The treasuries go from the hedge fund to the bank, and this increases the size of their balance sheet.

They have the same amount of reserves but, more treasuries also increases the liabilities side, in the sense that they now gave the hedge fund an additional $250 dollars for that collateral.

So, the assets on the hedge fund's balance sheet, of course, is increased by that same $250 dollars.

That means that they have additional purchasing power. That is key.

In transaction #1 between the Fed And the primary dealer bank, we didn't change the number of deposits in the system. That means we didn't change the amount of purchasing power.

But in this example, we've gone from $1,000 dollars of deposits to $1,250 dollars in deposits.

Because this transaction was between a primary dealer bank and another entity in the private sector, in this case, yes, we do have more money injected into the system.

-

Transaction #3: Primary Dealer Bank A/Hedge Fund With An Account On A Different Bank

This example is between bank A and a hedge fund. But this time, the hedge fund has an account with a different bank.

The hedge fund still sends the treasuries to bank A, and they go on the asset side of the bank's balance sheet, but the size of their overall balance sheet does not change, they have fewer reserves.

Now they owe those reserves to bank B because that's where the $250 dollar deposit is for the hedge fund. But remember, this all happens on the backend, because their reserve accounts are with the Fed.

The way this looks is the Fed takes reserves from bank A's account and sends them into bank B's account. It all happens on the backend.

The only thing that happens on the front end is the $250 dollar deposit, which is created with bank B, and the treasuries go to the asset side of bank A's balance sheet.

-

Transaction #4: Hedge Fund/Stock Seller

This time the transaction is between the hedge fund and our new participant, a stock seller I'll call Steve.

So the hedge fund goes over to Steve and says, “Listen, we've got a deal for you. We want to buy $250 of your shares.”

Steve looks at the hedge fund and says, “Well, I don't know. You guys seem a little sketchy, but we'll go ahead and do the deal.”

The transaction starts with Steve having $250 dollars of shares as assets. The hedge fund has $250 dollars of deposits with their bank, bank B. And, we'll assume that Steve bank is bank A.

After the transaction is done, Steve now has $250 dollars of deposits, the hedge fund has those $250 dollars of shares, and the deposits in the reserves go from bank B, just over, to bank A.

On the backend, remember, the Fed simply takes the reserves from bank B and puts them into bank A's account, for $250.

The main takeaway to understand how it works is that all the transactions we see on the New York Fed's website, the repo operations, are between The Fed and the primary dealers.

That means that there are no additional deposits being created, unless the commercial banks do so themselves.

The Fed could take their balance sheet up to a hundred trillion dollars, and it wouldn't matter. And it also doesn't mean that liquidity is getting into the system.

The commercial banks have to take that additional liquidity or additional reserves and turn those into more deposits.

Then the people or the entities that have those additional deposits can take them and buy shares in the stock market, bonds, XYZ asset class.

The whole point is to remember that The Fed actually has very little control over the amount of liquidity in the system. The entities that have total control over that are the primary dealers and the commercial banks.

The Real Reason Why The Repo Market Operations Are Oversubscribed

What I hear in the media nonstop is there's a lack of liquidity or lack of reserves, and that doesn't make a lot of sense.

Look at the following chart I drew. If you look at the Fed's balance sheet, you can see $1.5 trillion in excess reserves on their liability side.

For those of you who haven't seen a lot of my videos, I'll fill you in on a little surprise.

Before the GFC, generally, there'd be about six or seven billion dollars in excess reserves. Now, as seen on this next chart, there is 1.5 trillion in excess reserves. So I have a hard time believing that is the root of the problem.

They say, “Well, the regulations with Basel III and with the G-SIB, also the LCR,” which is the liquidity coverage ratio, “that makes them hold more reserves.”

Yeah, but does it make them hold 1.5 trillion? I don't think so.

Also, the deficit people say, “Well, the government's been selling all of these bonds because Trump's running trillion-dollar-plus deficits, and the primary dealers are responsible for buying those bonds, those treasuries. They're the market makers.”

And all of that may be true, but if the primary dealers are buying all those treasuries from the government, that still depletes the excess reserves because the treasury has the TGA( treasury general account), which is a completely separate account with The Fed.

I've also been hearing in the media a lot lately that the oversubscriptions could be a result of COVID-19 because the banks are really getting freaked out, so they're trying to increase their levels of liquidity.

But, that doesn't make sense either, because the huge oversubscribed repos were in March 3rd of 2020.

So why, if the banks wanted more liquidity because of COVID-19 would they just start March 3rd, when last week, the market went down by 12% because of that same reason?

Or, it could be a collateral issue, which I think is far more likely.

The way that would play out is like this. We would have three issues:

-

Lack of reserves

Bank C needs some cash, but unfortunately, they don't have any “pristine collateral”, which, believe it or not, the market considers to be treasuries.

All they have are subprime auto loans. So Bank C calls up their buddies at bank B and says, “Listen, guys, we've got a little problem. We need cash, we don't have treasuries, let's do a little swap really quick.”

-

The collateral problem

The guys at the bank say, “Yeah, fine. Okay. Whatever.” So they swap that collateral, bank C takes the treasuries and goes right to The Fed.

But, the Fed has no idea that those treasuries are backed by subprime auto loans. So they take the treasuries, and give bank C the reserves that they need, and bank C is free and clear. They are good to go.

If this happens in mass throughout the entire banking system, where they have a lot more of this garbage collateral, that would force more of the banks to go to The Fed and get their repo transactions done there, creating an oversubscription.

What it really boils down to is the Fed would be the only one that was stupid enough to take that collateral that really wasn't the bank's to begin with.

-

Counterparty risk

This is pretty straight forward. Bank A is almost insolvent, B and C know that well.

So, if The Fed wasn't involved, bank A would have to go to the other banks and say, “Listen guys, we need cash.”

They would say, “No way. We're not taking the risk”, and they'd basically give them the Heisman. Bank A has to go to the Fed because the Fed doesn't have to worry about profit or loss.

Bank A gives them the treasuries they do have, and they get the liquidity from The Federal Reserve. For the moment, the problem is solved.

You may be saying to yourself, “Yeah, George, I get it. But…

A couple of banks running into problems, is that really going to create the oversubscribed repo operations that we've been seeing lately?”

What I need to remind you is that the repo market is much greater in size than what we see with the New York Fed's website.

The repo market has $2.2 trillion of transactions every single day.

Even if a small fraction of those transactions are having problems, that is going to lead to The Fed's repo operations being massively oversubscribed.

What I've been saying is it's really about The Federal Reserve and the government versus reality.

They're in this battle for confidence, whether it's consumer confidence, confidence that the stock market will always go up, or confidence in the $2.2 trillion a night repo market.

If the Fed and the government lose the battle of confidence, that last Jenga piece goes. Then, it is really stiff drink time.